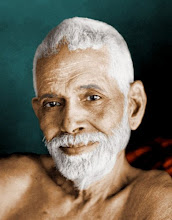

David Steindl-Rast was born in Austria in 1926 and grew up under the Nazi occupation. He earned a PhD in art, anthropology, and psychology from the University of Vienna before coming to America with the hope of earning a fortune. This plan was derailed when he read “The Rule of Saint Benedict” and realized that his life path lie elsewhere. He joined a Benedictine monastery in Elmira, New York and has been based there for over fifty years, becoming renowned for his efforts to promote communication, understanding, and cooperation between the world’s great religious traditions and to foster the evolution of Christian contemplative thought and practice through what he calls “mysticism in action.”

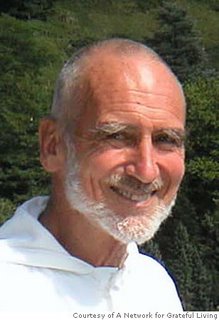

In this week’s featured “Integral Naked” interview with Ken Wilber, Brother David laments the resistance of Christian institutions and individuals to deeper spiritual realization and personal transformation and argues that the shallow biblical literalism of Christian convention must be supplanted by a more enlightened “Godview” grounded in direct spiritual experience properly interpreted by the intellect. He and Wilber agree that Christianity would do well to embrace some form of “evolutionary panentheism” in which a spiritual force or essence is seen as causing, comprising, and encompassing all of Reality and as steering development of that Reality, especially as manifested by the higher consciousness of human beings, toward self-realization. Steindl-Rast argues that the seeds of this development in Christian thought lie in the Trinitarian doctrine of God as Father, Son, and all-pervading Holy Spirit.

In 1947, Alan Watts was an Episcopal priest who wrote a book entitled ‘Behold the Spirit: A Study in the Necessity of Mystical Religion.’ It was a remarkable expression in its or any other time of what Wilber and Brother David call “evolutionary panentheism” in Christian terms. But Watts left the Church a few years later after coming to the painful realization that institutional Christianity and the masses of people subscribing to it were unlikely to come around to his point-of-view within the foreseeable future. He also realized that even though it might be theologically possible to reconcile Christianity with panentheistic mysticism, one had to go to such “tortuous” intellectual lengths to do so that it was wiser to count his losses and leave the Church to walk his own spiritual and philosophical path than to go on trying to put the “legs” of Christian theologizing on the “snake” of mystical insight.

Of course, Steindl-Rast has been “Brother David” for far too long to officially leave the institutional fold now. But I wonder if he didn’t unofficially stray from the fold of foundational Christian thought and experience a long time ago, and if his efforts to foster the evolution of Christianity from within aren’t doomed to fail.

For every Christian Church with which I’m familiar teaches that God made the universe and everything in it much the way a toy maker might fashion a dollhouse and its contents; that “He” sent his one-and-only “son” to Earth to save us from our sins by living a perfectly sinless life, by dying an agonizing death on the Cross to atone for our sins, and by then being bodily as well as spiritually resurrected to reunite with his “father” in heaven; and that one must, at bare minimum, believe in these things literally to be a true Christian. And all the people I know who call themselves Christian do believe or try to believe these things. And try as he might, I don’t see how Brother David can ever reconcile this mindset and “Godview” with that which not only intellectually understands but also feels in the deepest possible way that we and the universe are part of the living and ever-evolving body and soul of God. These perspectives simply seem too far apart to be bridged by other than prodigiously gifted minds exerting Herculean effort to graft superfluous and ill-fitting legs onto a snake.

Is it truly worth the bother?